SIT TIBI TERRA LEVIS

may the earth be light for you

Spring 2022

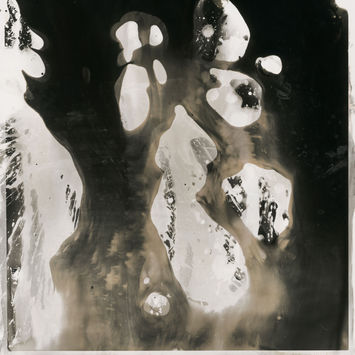

These photographic prints were processed like our bodies are processed after death. I brushed some with oil just as the ancient Greeks would’ve anointed their dead. Some, echoing the traditions of ancient Babylonians, I soaked in honey. One, encased in salt as the ancient Egyptians. For others, I simulated modern American practice of chemical embalming by washing the prints with soap before processing them with different combinations of photographic chemistry. Some of these are incompletely fixed, meaning they will continue to decompose and degrade over time. Others were soaked in fixer for days, leaving stains on the print as if it had been aging slowly for years.

Includes inscriptions from ancient Roman tombstones

I never really knew my father’s father. He left behind only old cassette tapes, stories, and glimpses of memory from before he got sick. He had a rare genetic disease that killed him slowly, piece by piece, neuron by neuron. I remember playing hide and seek with him behind the cascading fabric roses in our living room, and I remember him rocking in his armchair, gently humming a song I didn’t recognize. I remember the smell of the hospital room where he died. I was 12. He was 67. Did my father have the same disease? Would he die just like his father- would I die just like him? I can’t remember the color of his eyes or the way he hugged me, the sound of his voice or how he laughed. Slowly, piece by piece, neuron by neuron, he disappears from my mind. Would I die just like him?

Whenever my sister and I drove past a graveyard, we held our breath. I don’t know who taught us this game, but we played every time we sat together watching the world through glass and parallax. Small churchyards and cemeteries required only a few seconds without breath, but sometimes the graves went on seemingly forever, covering the rolling hills with names remembered and forgotten. Sometimes we had to hold our breath for minutes that stretched on for eternities. I could feel my heart pushing against my skin, calling out for air. We sat in the backseat silence, breathless as the dead outside the window, with hearts pounding urgent.

Sometimes I walk through the woods in Starlight. The telephone birds warble in the leaves overhead, rustling as the wind gently breathes through the branches. Cicada song drowns the train whistles that echo up through the valley. Sometimes I sit by a stump with miles of roots buried under the mushroom laced moss: once it stretched above the clouds, now it rests below the earth. Sometimes surrounding trees share their water with the stump, but not enough to help its branches grow back. Is it dead or alive? Is it alive or dead?

There was a hole in the ceiling of my grandmother’s old house. We were not allowed to climb up: too dangerous, my grandmother would say. But once, we felt brave, and pulled the small white string that revealed the pathway up to the attic. We tiptoed across wooden beams that split seas of mothballs and dust; we hid in racks of old coats and evening gowns. Amid the stacks of cardboard, we found a small shoebox filled with ghosts. The people on the countless decaying pages stared at us as we admired them. They were alive then, staring at the camera, laughing, smiling, full of dreams, full of heartache. Like us. But now they are dead. They are empty and motionless somewhere below moonwort and forget-me-nots. Like we will be. But still they stare at us, immortal in paper and silver and gelatin.

breathe in